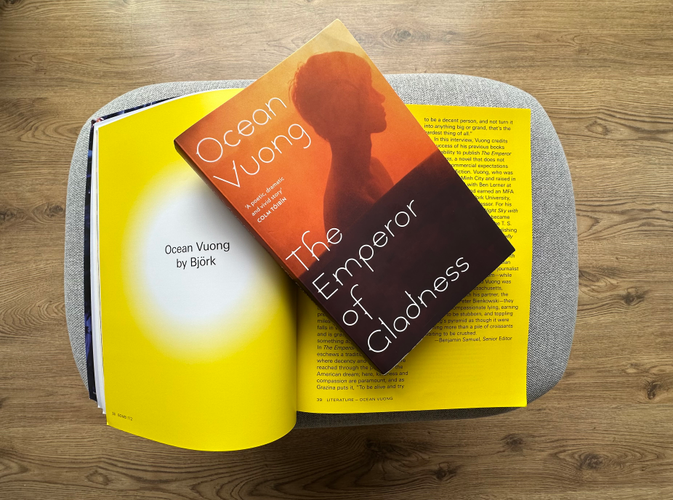

booklog: The Emperor of Gladness

In 2025 I read The Emperor of Gladness by Ocean Vuong.

Timeline

- Sep 15, 2025: started reading.

- Sep 23, 2025: finished reading.

Review

I have to admit that I picked this up primarily out of morbid curiosity. Tom Crewe’s piece in LRB made me want to know if it was really so bad. I also listened to interviews with Ocean Vuong and read some of the criticism of the criticism.

Four hundred pages later, here’s where I am: I did not enjoy reading this book. I think I may have enjoyed reading the book that Ocean Vuong talks about in his interviews. But the aspirations of the artist do not appear to have made it to the page.

Of course, there’s a chance that Vuong is writing outside of the tradition I am most familiar with. This is often brought up by defenders of the novel, but these counter arguments rest on theories of fiction and narrative frameworks. And none of them point to anything in the prose that adequately supports them — at least, none of the ones I have found.

There’s this trend in publishing where people emphasize a book being “written by a poet.” Often it serves as an important part of the marketing plan when a novel is published. I think the reason publishers lead with it is because it carries with it the assumption that poets, more so than your typical prose writer, will agonize over ever syllable, simile, and metaphor in the book. That they’ll invent new forms to hold their unique vision of the world, rather than stick to rote or prescribed rules of narrative. And this is maybe what’s most frustrating about this book. It is so generic and unconsidered in almost every way. The relationships that are supposed to anchor the lack of action feel one-dimensional and inauthentic. The “comedic set pieces” feel dropped in and unearned. Even when he’s reaching for lyrical images, they come across as forced and heavy-handed.

For what it’s worth, though, I don’t think I’d forgive even a non-poet novelist for writing the simile: “two fast-food workers in a shrink’s office, like a New Yorker cartoon caption contest.”

At the end of the day, there was almost something here. There were several places in this book where you could see Vuong reaching for something more insightful, more profound, only to watch him trip over his own unchecked sentimentalism. Maybe I’m wrong. Maybe history will look back at this book and judge it more kindly. Right now, though, it feels like Vuong’s editors assumed they had a hit and didn’t read the manuscript too closely.

Details

- Publisher: Jonathan Cape

- Page Count: 397

- ISBN: 9781787335417

<< shelf.