booklog: Jacques the Fatalist

In 2025 I read Jacques the Fatalist by Denis Diderot.

Timeline

- Jul 07, 2025: started reading.

- Jul 29, 2025: finished reading.

Review

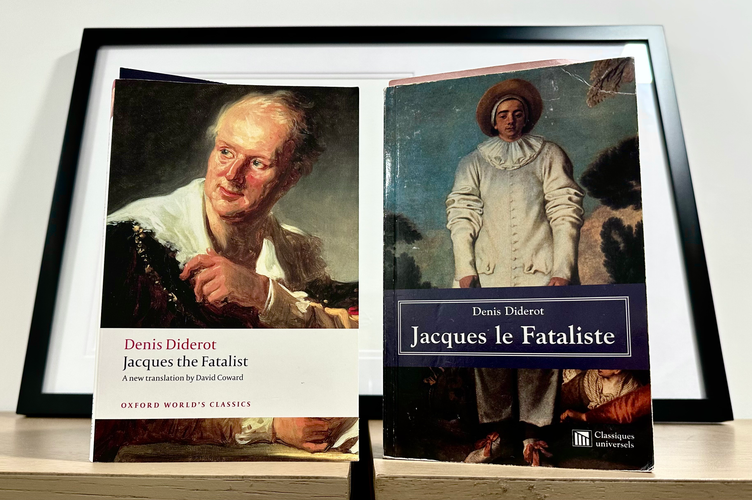

In the interest of full transparency, I’ve tried and failed to read the full text of Diderot’s 18th century exploration of fate, free will, and the conventions of narrative form on and off since roughly 2010. Part of the problem was that I was trying to read in the original French. This in and of itself isn’t necessarily an insurmountable hurdle for me. However, the copy I owned was just a brief introduction and then the text. More often than not I was tripped up when I came across some old scrap of idiom that I wasn’t familiar with or a dated cultural reference that was completely unknown to me. As a result, I would often lose momentum and question why I was putting myself through this experience.

Fortunately, all of this changed once I picked up a copy of David Coward’s English translation. Not only did the extensive end notes and explanations come to my aid whenever I was at risk of drowning under mountains of misunderstood references, but his version finally helped me understand — more emotionally than intellectually, because this was something I knew but couldn’t quite grasp as I read the French — just how playful and funny Diderot’s prose is. Of course, though, this also left me with doubts about my own ability to read and appreciate the nuances of written French. I consoled myself by reading the English side by side with my original copy. Occasionally, I would read an especially flowery bit of archaic British idiom and turn to my French copy only to discover that Coward allowed himself to reach for the something more playful or unexpected.

I don’t advertise it much, but as an undergraduate I earned a certification in Translation Studies (specifically literary translation), and there was a not inconsequential amount of time in my early adulthood where I thought I might become a literary translator of experimental fiction. Of course, these thoughts quickly evaporated the first time I sat down and calculated the total debt I had shouldered as a consequence of my degree(s). (An event which led, ultimately, to a winding career in IT consulting and software engineering instead.) Nevertheless, being able to read an original and a translation side by side like this, to see the decisions a translator made either to embellish, standardize, or make the original more legible to a foreign audience still fascinates me.

But, Reader, you are probably asking what my impressions of Diderot’s text were. Fear not, now that I have dispensed with personal anecdotes I shall meet your expectations head on.

The story and its telling still feel unconventional +250 years after the book was written. Diderot is very much an artist at play here. Experimenting with form, tone, and gleefully subverting the expectations of his readers — even going so far as to put words into your mouth and then tell you that you are a fool for asking such questions.

The meandering protagonist and his master discuss weighty subjects, they discuss frivolous subjects, they get sidetracked by digressions, they forget where they left off. It’s somehow both a masterclass in the minute detail necessary for realism and a rebuke of it.

What can I say? Read the classics. You won’t regret it. Or maybe you will, but, as I’m sure Diderot would tell you, that’s your problem, not his.

Details

- Publisher: Oxford University Press

- Page Count: 258

- ISBN: 9780199537952

<< shelf.