Last Year's Reads

🗓 posted Jan 27, 2022 by Josh Erb🔢 2314 words

🏷 #review #fiction #non-fiction

Some background

As a personal rule, I set a goal of reading at least two books a month each year. I've done this since college, and I've found that it's the one goal I really enjoy sticking with every year. Without exception.

This past year (as well as the previous one) I actually to exceed my goal by a handful of books. There are no silver linings to a pandemic, but this is one positive note in what have been two really shitty years: this multi-year pandemic we've all been living through has given me a lot of time to sit around and read. One of the least risky ways to keep yourself sane and healthy when a deadly virus is isolating you and wreaking havoc on your community is to sit down with a tall mug of mint tea and a good book.

So here is a high-level break down of the books I sat down with last year, grouped into arbitrary genre categories I just made up off the top of my head:

| Genre | Number of Books | Pages |

|---|---|---|

| Fiction (non-U.S.) | 8 | 2,459 |

| Non-Fiction | 8 | 2,209 |

| Fiction (U.S.) | 6 | 1,919 |

| Philosophy | 5 | 928 |

| Alternate History | 2 | 592 |

I'm glad to see that fiction originally published outside of the U.S. is so well represented. Americans tend to miss out on a lot of interesting writing because we only read things written and published in English. I'm also surprised to see that I read so much non-fiction. I've often joked that I don't trust anyone who exclusively reads non-fiction, and it's not something I instinctually reach for in my free time.

Anyway. Enough navel gazing. As a fun exercise, I wanted to include a link to the cover to each book and give it a one to two sentence review based on my recollection. I'll do this below in the order that I read each book.

Reviews

No Shortcuts by Jane McAlevey

A bit academic and dry, but that's to be expected since it's an adapted doctoral thesis. Otherwise, very instructive read.

Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature by Richard Rorty

I have to be honest, I started reading this a few years ago and set it down. I only picked it back up when I had some free time at the beginning of the year. Rorty is a virtuoso of philosophical thought in this seminal work. He demonstrates a thorough understanding of the western philosophical canon over the last several centuries, and then proceeds to explain why he disagrees with almost all of it. Dense and thorough, but there's a lot in here that I'll be thinking about and returning to for many years to come.

End Zone by Don DeLillo

Even minor DeLillo is a cut above the rest.

Everything in this book collides with everything else; language, form, function. Intimacy and knowledge are only possible through the pain of contact, the destruction of the self.

Dancer by Colum McCann

I read McCann's Let the Great World Spin a few years ago and loved it. So I came into this one with high hopes.

Unfortunately, he didn't quite hit the mark. It had some really great passages, most notably the opening description about families waiting in Siberia for local soldiers to return home from the World War II front, and there's no denying McCann's talent with the pen. However, in this case, it felt as if he were trying to shoehorn his story into a structural formula because he feels most comfortable with that formula, and not because the style was well suited to the story.

Life: A User's Manual by Georges Perec

This is simultaneously one of the most original and fascinating books I have ever read and one of the most tedious.

I don't regret reading it, and there are many passages that stayed with long after the reading, BUT I can't in good conscience recommend a book that itemizes ever single item in every single room of an apartment building in Paris to anyone I consider a friend.

Mules and Men by Zora Neal Hurston

This felt like two distinct books. The first section is interesting, though a bit of an odd mashup between dry, anthropological study and splotches of colorful scene setting. The reasons for these characteristics, of course, are confirmed in the essay on the book’s rough road to publication included in the afterward.

The second section on Hoodoo practices in New Orleans was way more compelling than I expected. Definitely not for the squeamish, though.

Fire on the Mountain by Terry Bisson

This slim novel was a pleasure to spend time with. Anyone interested in a radical re-imaging of the bends the road of American history might have taken should pick up this book.

Work Won't Love You Back by Sarah Jaffe

This book was selected as part of the Mapbox Workers Union's book club in the lead up to our campaign going public. It's a stern look at the state of work in the U.S., but Jaffe also manages to slip in hope and optimism despite the dismal state of things. It's not the end all and be all of labor writing, but definitely a relevant one to pick up when you need some grounding.

Mortal Engines by Stanisław Lem

This collection wasn't published in Lem's lifetime, and that shows a bit in how uneven the stories feel. It's Lem, so it inevitably has some dazzling and inventive moments. (I'm still in awe of the the brilliance of a Cyber Knight on a planet made of ice doing his best not to think, lest he heat up and melt through the surface and down into its core.)

If you're only going to read one to two books by Lem in your lifetime, first of all how dare you??, but secondly, maybe skip this one. But if you're a completist, as almost everyone eventually becomes, it's still a fun romp through Lem's twisted, comedic world of cyber fables.

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass by Frederick Douglass

I love it when a book I read inspires me to pick up another, such a direct journey on the web of intertextuality is thrilling. This one ended up on my list after I read Fire on the Mountain earlier in the year and was made acutely aware that, although I have a vague notion of Frederick Douglass as a historical figure, I have not taken the team to understand him on his own terms. In his own words.

This first of his autobiographies is brief, but you feel the urgency with which it was written by the young Douglass. The personal perspective it presents on chattel slavery in the antebellum U.S. is direct and more nuanced than I had initially expected.

Babbit by Sinclair Lewis

A send-up of the emptiness of a life lead under the direction of consumerism and unreflective pursuit of success in modern business. It's almost over 100 years old and the only thing that feels outdated is that the protagonist has to crank his car to get it started.

Frankenstein in Baghdad by Ahmed Saadawi

Eerie. Horrific. Heartbreaking.

The City & the City by China Miéville

The premise is ingenious. It poses a lot of interesting questions about our ways of seeing one another in the cities we call home. The city in question could be Washington, D.C. It could be Chicago.

Unfortunately, while the premise is one of the most thought provoking I've read in quite some time, Miéville fails to stick the narrative landing and I set the book down feeling unsatisfied.

The Art of Asking Your Boss for a Raise by Georges Perec

A nice bit of experimental fiction. Love that the structure and flow of the narrative is modeled after a computer program.

The Present Age by Søren Kierkegaard

I really have to be in the right mood to enjoy Kierkegaard. If I'm being honest, I enjoyed the playful, smirking introduction og Walter Kaufmann more than the two essays that were meant to be the bulk of this publication.

The Southern Question by Antonio Gramsci

Gramsci is an interesting historical figure. I wanted a brief introduction to thought and writing. I got it, but I can't say that I've retained much after reading this brief pamphlet.

(And to set the official record straight: this stickered-up cover is the result of my using the Open Library Covers API.)

Utopia by Thomas More

Like almost all prescriptive utopian fiction, More’s book piques your interest at first because of its critique of the contemporary culture in which it was written - but ultimately becomes tedious as it attempts to describe a better way of doing things. (Which, I might add, did not age well with its over-reliance on slavery and mercenaries in order to preserve the sensibilities of its citizenry.) Though, it’s worth reading if only for its foundational place in the western literary cannon and its introduction of the concept of utopia.

Anyway. More’s novella is fine, but the edition I have includes essays from Ursula Le Guin & China Miéville. These addenda were insightful and improved the overall experience of engaging with this work.

Beaten Down, Worked Up by Steven Greenhouse

It's written by a veteran labor journalist, and it very much reads like it. That being said, this book taught me a great deal about the 20th century American labor movement. Spoilers: as Greenhouse gets closer to the recent history of the American labor movement, things start to get depressing.

Favorite fun fact: the first female cabinet secretary was FDR's Secretary of Labor Francis Perkins.

Anarchist Communism by Peter Kropotkin

(Open Library does not appear to have a copy of the cover of this slim little edition.)

This is a brief extract from Kropotkin's larger work The Conquest of Bread. It was much more readable than I expected. Nice introduction to Kropotkin’s thought. I'm excited to read more.

Civilizations by Laurent Binet

It's nice to throw a French language book into my rotation every once in a while. I devoured this book during a late summer vacation, while I was sitting next to a lake in West Virginia. The premise pulled me in, even though bits of it felt a bit tenuous. The fantasy of a world where there currents of imperial power flow in opposite directions is an interesting one to explore and Binet does a great job.

This was just published in English late last year, which means the clock is ticking on it being turned into a long-running television series. I'd recommend reading this now before some clumsy American producers beam their own interpretation into your eyeballs.

The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel

I feel like this had real potential. The writing is great, the story left a lot to be desired. Every interesting theme or story line was left frustratingly underdeveloped.

A Nation of Women by Luisa Capitello

Interesting from a historical perspective. Badly dated as a political treatise. Anarcha-feminism meets The Secret.

The Cyberiad by Stanisław Lem

It's Lem. What can I say? Humorous. Profound. Wildly inventive. I have never regretted any time that I've spent reading his stuff.

Ways of Seeing by John Berger

I wish I had read this book sooner in life. A quick read, but each section is packed with insight into how we perceive the world around us. Very highly recommended, which is surprising since it's the book adaptation of a BBC special from the '70s.

The Book of Ten Nights and a Night by John Barth

I've read a bit of Barth's other work (e.g. Lost in the Funhouse, Chimera), so I had a sense of what to expect. Unfortunately, it appears that early Barth is much better than late Barth. Almost each and every story in this collection is concerned with extremely banal formulas and obsessive mid-flight naval gazing and deconstruction.

I fear that this has put me off of his writing for a bit.

Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead by Olga Tokarczuk

Tokarczuk is one of the most talented living authors in the world today. This book is exceptionally well done, a master class in writing a sympathetic, unreliable narrator. One of the best novels I've read in recent memory, maybe ever.

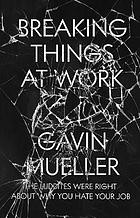

Breaking Things at Work by Gavin Mueller

I picked this up expecting it to be a brief history of the Luddite movement, and an attempt at correcting the narrative that's festered in the popular consciousness. Meuller briefly does this, but then eagerly transitions into a manifesto of sorts for building a contemporary neo-luddite. I was surprised, but not disappointed.

Homage to Catalonia by George Orwell

"I have the most evil memories of Spain, but I have very few bad memories of Spaniards."

I had been meaning to pick this one up for a while. It found me at the right time. Interesting insight into the Spanish Civil War, told by someone still struggling to understand what happened and the role he played in it.

The Ways of White Folks by Langston Hughes

Prior to reading this, I had thought of Hughes primarily as an extremely talented poet. I now see that he was also an extremely talented writer who saw the world around him with clear eyes.

Ever single one of the stories in this collection will punch you in the gut.

<< all notes.